Raising the Banner of Freedom: The Struggle for the Novorossiysk Republic

Many of us have, at least once in our lives, walked along the street of the Novorossiysk Republic—one of the most picturesque and historically intriguing locations on the shores of Tsemess Bay. And of course, we are all familiar with the monument standing there, a silent reminder of events that took place more than a century ago.

Throughout its long and eventful history, our city has taken on many forms. It was originally founded as the ancient Greek colony of Bata. Later, at different times, it served as the trading base of the Genoese merchants known as Batario and as the Turkish military fortress of Sudzhuk-Kale. Then, as part of the Russian Empire—under its present name—it evolved from a small provincial town into a gubernatorial administrative center. During the Soviet era, it grew into a major transportation and industrial hub, a role it continues to fulfill to this day.

Only a modest monument on the street of the Novorossiysk Republic reminds us of those now somewhat forgotten times when our city was an independent state. Yes, you heard that right—such a chapter exists in the history of Novorossiysk! Though this republic lasted for only a short time—just two weeks at the end of December 1905—it left a vivid mark on the history of revolutionary struggle in our country.

A deeper understanding of those events can be found in the documentary memoir Novorossiysk Republic by Vladimir Dmitrievich Sokolski. The book’s greatest value, in my opinion, lies in the fact that it was written by someone who directly participated in those events.

Vladimir Sokolski was born in the 19th century, in the year 1883. From his youth, he actively participated in the struggle against autocracy. After the suppression of the Novorossiysk uprising, Sokolski, who was known in the revolutionary underground by the alias "Boris," was sentenced to death in absentia. For several years, he evaded persecution by Russian authorities, hiding in Moscow, Dvinsk, and Tver. In 1909, he managed to escape to Persia (now Iran), where he worked for a long time as a teacher at a Russian school.

After the October Revolution, Sokolski returned to Russia. During the Civil War, he headed the Department of Public Education in Samara, and later, until the end of his life, he taught at various Soviet universities.

Sokolski completed work on his manuscript, Novorossiysk Republic, just days before his death. As a result, he never saw his monograph published in its final form.

His posthumously published book is not merely a vivid memoir from one of the participants in those harsh events, but also a serious scholarly study based on numerous archival materials and periodicals from that era.

Unfortunately, Novorossiysk Republic, printed more than half a century ago, has never been republished—today, it can probably only be found as an exhibit in the Novorossiysk Historical Museum.

That is why we wish to tell our readers about this small but significant book, even if only in the form of this article in our almanac. After all, chances are you won’t be able to find it anywhere else.

Prerequisites

In 1905, our city—then not yet a "hero"—like the rest of Russia, was going through extremely harsh and turbulent times.

First, Tsar Nicholas II was rapidly losing the prolonged war with Japan—a neighboring country that, as we all remember well, he had planned to "crush effortlessly" in just a few days.

Second, a powerful protest movement was gaining momentum across Russia. A vast number of people, who had already been living and working under difficult conditions while earning meager wages, became even poorer. The ruinous and senseless war led to severe economic problems in the country.

Third, these events made it glaringly clear that the corrupt and morally decayed ruling elite was no longer capable of governing the state.

The situation was further aggravated by the sheer disregard officials showed toward ordinary people. As one particularly striking example of this, Vladimir Sokolski recalls Balka Adamovich.

For the modern generation of Novorossiysk residents, this name is most likely associated with the events of 1942, when two battalions of marine infantry halted the advance of German-Romanian troops there and heroically held the line for nearly a year, preventing the fascists from breaking through to the Caucasus.

However, had you lived in our city not in the mid-20th century but at the beginning, Balka Adamovich would not have seemed remarkable, let alone heroic. It was a poor and unfavorable settlement in every respect, located on the eastern—industrial and most polluted—outskirts of the city.

Almost all the land in that area had been bought up by a high-ranking general, Adamovich, from St. Petersburg. He used it to generate exorbitant rental profits but did not invest a single penny in infrastructure or development.

As a result, the entire area he owned became densely packed with tiny, dilapidated huts, rented out as housing for the workers of Novorossiysk’s factories. These workers had no alternative, as housing shortages were a constant issue in the city—something General Adamovich readily exploited.

Thus, in the settlement bearing his name, there were no roads, no street lighting, and no water supply. No schools, hospitals, or libraries were built there.

To put it bluntly, these were foul-smelling slums where only three things thrived—crime, unsanitary conditions, and the ever-rising cost of rent for even such deplorable housing.

And there were dozens of similar settlements surrounding Novorossiysk. Naturally, each one of them became a breeding ground for growing discontent with the prevailing conditions.

The Beginning

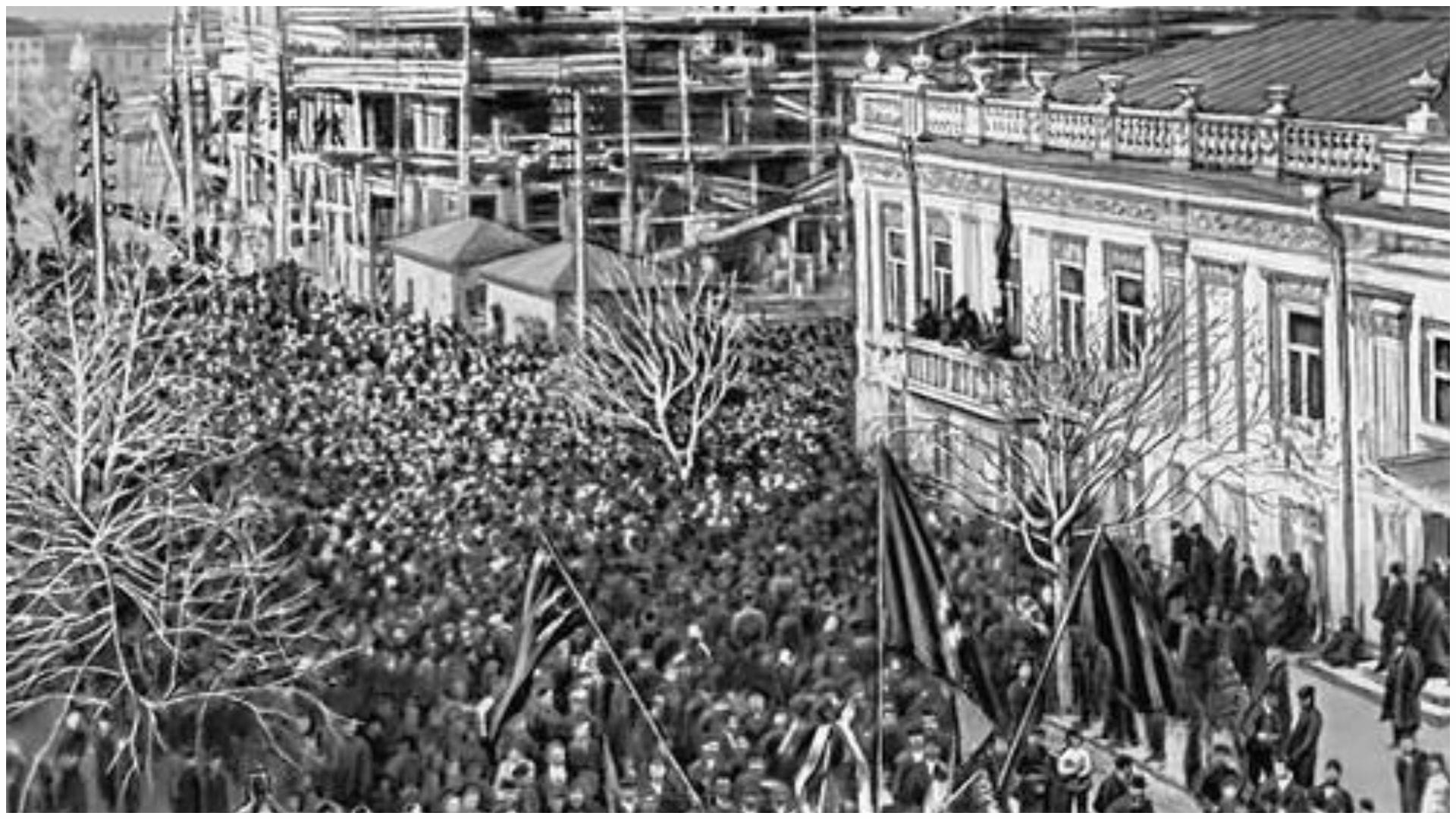

The first battle against the tsarist enforcers and the corrupt city officials on the shores of Tsemess Bay took place during a massive demonstration on May 1, 1905.

Notably, the Novorossiysk demonstrators did not repeat the mistake of the St. Petersburg workers, who had been ruthlessly crushed after humbly presenting their petition to the tsar on January 9 of that same year. Instead of starting with a naïve peaceful protest, the people of Novorossiysk launched their struggle with decisive and forceful actions from the outset.

Almost all the participants in the march were armed—not only with makeshift daggers and pikes but also with firearms, which had, of course, been acquired illegally. Thus, when the so-called "hundred"—a cavalry squadron of Cossacks deployed by the authorities to disperse demonstrations—attempted to approach, the protesters immediately fired several warning shots in their direction.

The following is a direct quote:

"It caught the Cossacks completely off guard. They turned their horses around in disarray. Their commander was unable to stop the retreat and was seen galloping behind the squadron. The Cossacks never appeared on the city streets again. The police posts seemed to have been washed away by a tidal wave."

Thus, the people of Novorossiysk held their rally unhindered near the city Duma (parliament) building, after which they proceeded to the prison and freed a political prisoner who had been arrested the previous day.

Despite the intensity of the confrontation and the two-day strike that followed the May Day demonstration, not a single demand of the Novorossiysk protesters was met. The authorities did not reduce the twelve-hour workday to eight hours, did not raise wages, and did not introduce mandatory health insurance. Moreover, they demonstratively refused to fulfill even the most trivial symbolic demands, such as opening free public baths or providing heated facilities at industrial enterprises.

The consequences of the May Day demonstration of 1905 had a profound impact on the worldview of the people of Novorossiysk. On one hand, they were once again deeply insulted and angered by the authorities’ blatant disregard for them. On the other hand, they no longer feared or respected those in power.

A natural result of this shift in mass consciousness was that in the following months, protest sentiments in the city grew rapidly, with street demonstrations and revolutionary rallies becoming more frequent. Many of these protests were no longer coordinated with the city administration, as the opinion of the official authorities had already ceased to concern most people.

There is no need to dwell in detail on all the major strikes and protests in Novorossiysk throughout 1905, which are thoroughly described in Vladimir Sokolski’s book. There were many of them, they erupted for a variety of reasons, were organized by representatives of different socio-political movements, and involved a broad spectrum of the population—from students to soldiers, from women to workers, and so on.

By the end of autumn 1905, Novorossiysk had developed an almost ideal revolutionary situation. The citizens felt like the absolute masters of the streets, while local officials and law enforcement agencies were confused and deeply demoralized.

A telling example of this is the fact that in early November, the then Black Sea Governor, Vladimir Onufrievich Trofimov, simply fled from Novorossiysk to Tiflis, handing over his authority to his deputy, Alexei Alexandrovich Bereznikov. However, a month later, Bereznikov himself fled, hiding in a freight car at the railway station.

In early December, he received intelligence reports indicating that a large armed uprising was being prepared in Novorossiysk. Assessing the forces at his disposal, he rightly concluded that he would not be able to suppress the rebellion.

The Republic

Thus, in the first half of December 1905, the city of Novorossiysk—the administrative center of the Black Sea Governorate of the Russian Empire—was left effectively without any governing authorities.

Local initiative groups quickly took advantage of this situation. On December 13, they held elections for the Novorossiysk Council of Workers' Deputies. The overwhelming majority of those elected were representatives of the city's factories, who constituted the most active and economically productive segment of the population.

It is worth noting that despite the ideological fervor and the often overly insistent emphasis on the role of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in these events, Sokolski’s book cannot conceal the fact that the new city parliament was not exclusively Bolshevik. It also included Mensheviks, Socialist Revolutionaries, anarchists, and even two followers of the philosophical teachings of Leo Tolstoy.

Thus, the Novorossiysk Council became—without exaggeration—a genuinely democratic and highly inclusive governing body. Among its first decisions was the proclamation of a self-governing, independent state, free from central authority—the Novorossiysk Republic.

It is particularly important to emphasize that this new state on the shores of Tsemess Bay emerged entirely without bloodshed, as the local garrison refused to use weapons against the revolutionaries. As a result, there were no clashes with government forces.

Firstly, because the soldiers and police were well aware that the revolutionaries were armed and therefore fully capable of defending themselves.

Secondly, because they had personally witnessed how the tsarist officials and high-ranking commanders, fleeing one after another to save their own skins, abandoned their subordinates just as they had abandoned the rest of Novorossiysk’s population.

Thus, the government forces of the time had little inclination to risk their lives defending a hypocritical and collapsing regime.

From the very first hours of its operation, the Novorossiysk Council issued several key decrees:

- to close and dismantle all tsarist government institutions in its territory (except for banks, where workers received their wages);

- to implement an eight-hour workday instead of the previous twelve-hour workday at all industrial enterprises under its control and to raise wages;

- to release all political prisoners from Novorossiysk’s prisons;

- to introduce a progressive income tax on large business owners, among other measures.

Additionally, the new state proclaimed freedom of conscience, speech, and assembly. Independent courts were established, which began reviewing and overturning wrongful judicial decisions made under the previous regime. In particular, these courts actively reinstated workers who had been dismissed from their jobs for political reasons.

In summary, even at that distant time—more than a century ago—the people of Novorossiysk succeeded in establishing in their city a standard set of fundamental rights and freedoms characteristic of any modern democratic state.

Defeat

Unfortunately, as Sokolski notes, the people of Novorossiysk did not have the opportunity to fully experience the taste of freedom and democracy. On December 24, the tsarist government dispatched a large punitive detachment to the self-proclaimed republic, led by General Vladimir Alekseevich Przhevalsky (for clarification, this individual had no relation to his namesake, Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky, after whom a breed of Asian horses was named). At various points, the punitive detachment received naval support from Russian warships, Rostislav and Tri Svyatitelya (Three Holy Hierarchs).

Therefore, to avoid senseless bloodshed and to preserve revolutionary forces for future struggle, the Novorossiysk Council decided not to resist the advancing troops. It declared its own dissolution and, as of December 25, went underground. That same day, many civic activists in the city were arrested—and later repressed. Some were sentenced to death, though their sentences were later commuted to long prison terms.

In his book, Sokolski devotes considerable attention to the mistakes made by the leadership of the Novorossiysk Republic, which allowed the central authorities to seize the initiative and turn the situation in their favor.

First, after dissolving government institutions, the Novorossiysk Council failed to take adequate measures to arrest and neutralize high-ranking officials from the previous administration. Given that the Council had its own armed militia, it had every opportunity to do so at any time. As a result, Vice-Governor Bereznikov and his associates, having recovered from the initial shock and regrouped, were able—within a matter of weeks and with the support of the central Russian authorities—to organize efforts to suppress the uprising.

Second, the Executive Committee of the Council failed to recognize the necessity or did not deem it important to swiftly disarm the remaining army and police units in Novorossiysk. It was not until December 19—a full week after the republic was proclaimed—that the militia finally approached the head of the Novorossiysk military district and demanded that all available weapons be handed over.

By that time, however, he had already managed to remove the weapons from the city under the protection of Cossack troops. The next day, the militia made the same demand at the city police headquarters, but by then, no weapons remained there either. As a result, until the very last day of its existence, the militia of the self-proclaimed republic—which had to serve as both its army and law enforcement—was equipped with only a negligible number of rifles and revolvers inherited from earlier underground revolutionary struggles.

This lack of weaponry largely explains why the leaders of the uprising hesitated to engage in open battle with the well-armed, sizable government detachment sent to crush the Novorossiysk Republic.

Yet had the republic managed to hold out for even a couple of months—long enough for reinforcements from other revolutionary forces to arrive—the entire history of our city might have taken a completely different course.

Third, after achieving a temporary local victory in what was then still a relatively small city, the revolutionaries failed to take any steps to expand upon it.

It is worth noting that similar events were unfolding at the same time in neighboring Yekaterinodar (modern-day Krasnodar), and the Novorossiysk revolutionaries already had established communication with their counterparts there.

Nevertheless, they not only failed to coordinate efforts with their Kuban allies but also made no attempts to organize uprisings beyond Novorossiysk itself.

This was despite the fact that numerous suburban settlements were home to a large number of people who sympathized with and supported the revolutionaries in their struggle.

In Conclusion…

As we know, history does not allow for the subjunctive mood. The truly great and vivid chapters in the chronicle of our Hero City, unfortunately, can never be relived.

But let us remember them more often, as we gaze upon the majestic stele on the street of the Novorossiysk Republic, encircled by storm petrels frozen in gleaming metal—eternal symbols of righteous popular anger and great change…

You can download the text of this article in English or Russian at the link below.

The Golden Shelf of Novorossiysk

The third issue of the literary video almanac "The Golden Shelf of Novorossiysk", produced based on the materials of this article.

This article was also published in the Novorossiysk Historical and Local Lore Almanac "Istoki" named after Nikolay Turchin, No. 7, 2022, pp. 39–44.